On 26 July 1945 the Potsdam Declaration was issued by US President Harry S. Truman, the UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek during the Conference being held in Germany. This called on Japan to surrender or face ‘prompt and utter destruction’. No response was received from Japan’s Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki.

Group Captain Leonard Cheshire VC (RAF Museum PC76-23-31)

Group Captain Leonard Cheshire VC (RAF Museum PC76-23-31)

At this time Group Captain Leonard Cheshire VC, the skilled, courageous RAF Bomber Command pilot and legendary leader was working in Washington DC within the British Joint Staff Mission. A veteran of over 100 operations and former commanding officer of No. 617 Squadron, he had responsibility for tactical and technical development. He was told, in the strictest secrecy, about the $2 billion-dollar Manhattan Project and the creation of the atomic bomb. He was also informed that he would be one of the British observers if a bomb was to be dropped on a target in Japan. He was to learn about the ‘tactical aspects of using such a weapon, reach a conclusion about its future implications for air warfare and report back’.

Cheshire duly travelled to the western Pacific and arrived at the huge American air base on Tinian Island in the Marianas at the end of July 1945. He noted his inner conflict caused by ‘hope that the attacks would be postponed’ and an ‘obsession to see the bombs explode’. As preparations were made Chesire was able to see the bomb up close noting that ‘Hitherto the bomb had conjured images of devastating, unimaginable power…now I had seen it cut down to size…there was a potentially lethal side to it but equally an inert side that left it totally subservient to man’s will’.

At 2.45am, on 6 August 1945, a modified Boeing B-29 Superfortress of the USAAF’s 509th Composite Group took off from Tinian on a 2,526 km (1,570-mile) flight to Japan. The British observers were not allowed to fly with the group. The aircraft was piloted by the unit’s commanding officer, Colonel Paul Tibbets, and it was named ‘Enola Gay’ after his mother. At 8.15am, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress dropped ‘Little Boy’, a uranium ‘gun-type’ fission bomb, on Hiroshima. In an instant, 90 per cent of the city was destroyed and the first of 140,000 people were killed.

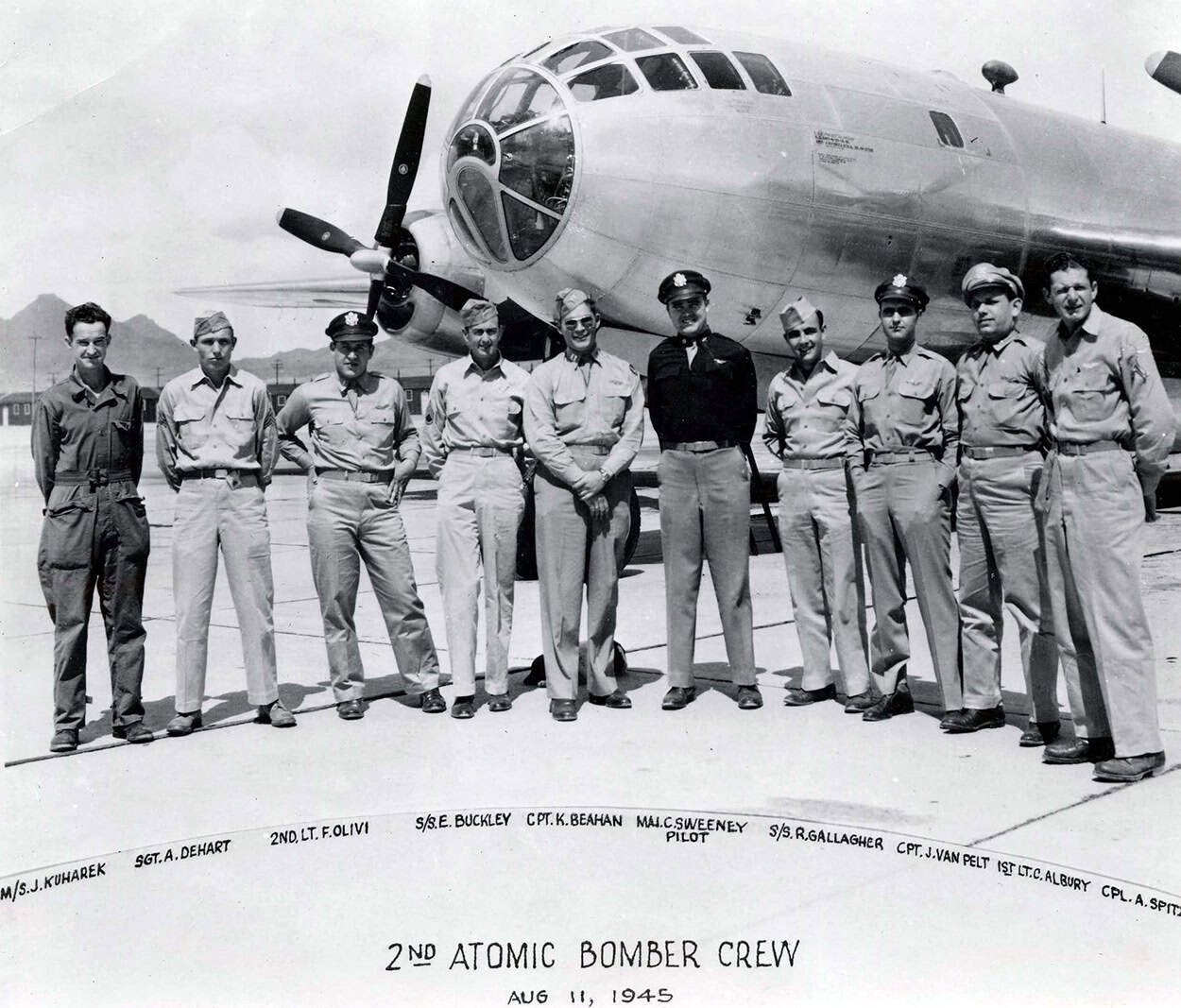

The Second Atomic Bomber Crew,

The Second Atomic Bomber Crew,

courtesy of the National Museum of the United States Air Force (060712-F-1234S-023)

With no response received from the Japanese authorities following this devastating attack, in the early hours of 9 August, Boeing B-29 Superfortress ‘Bock’s Car’, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, took off from Tinian bound for Kokura. The aircraft was armed with a plutonium implosion-type bomb codenamed ‘Fat Man.’ Finding the city obscured by cloud, Sweeney set course for the secondary target, the city port of Nagasaki, and dropped the bomb, which detonated at 11.02am.

This time Cheshire, was aboard the Boeing B-29 Superfortress camera plane ’Big Stink’, and witnessed the explosion from 50 miles away:

‘By the time I saw it, the flash had turned into a vast fire-ball which slowly became dense smoke, 2,000 feet above the ground, half a mile in diameter and rocketing upwards at the rate of something like 20,000 feet a minute. I was overcome, not by its size, nor by its speed of ascent but by what appeared to me its perfect and faultless symmetry…‘Against me’, it seemed to declare, ‘you cannot fight.’ My whole being felt overwhelmed, first by a tidal wave of relief and hope – it’s all over! – then by a revolt against using such a weapon.’

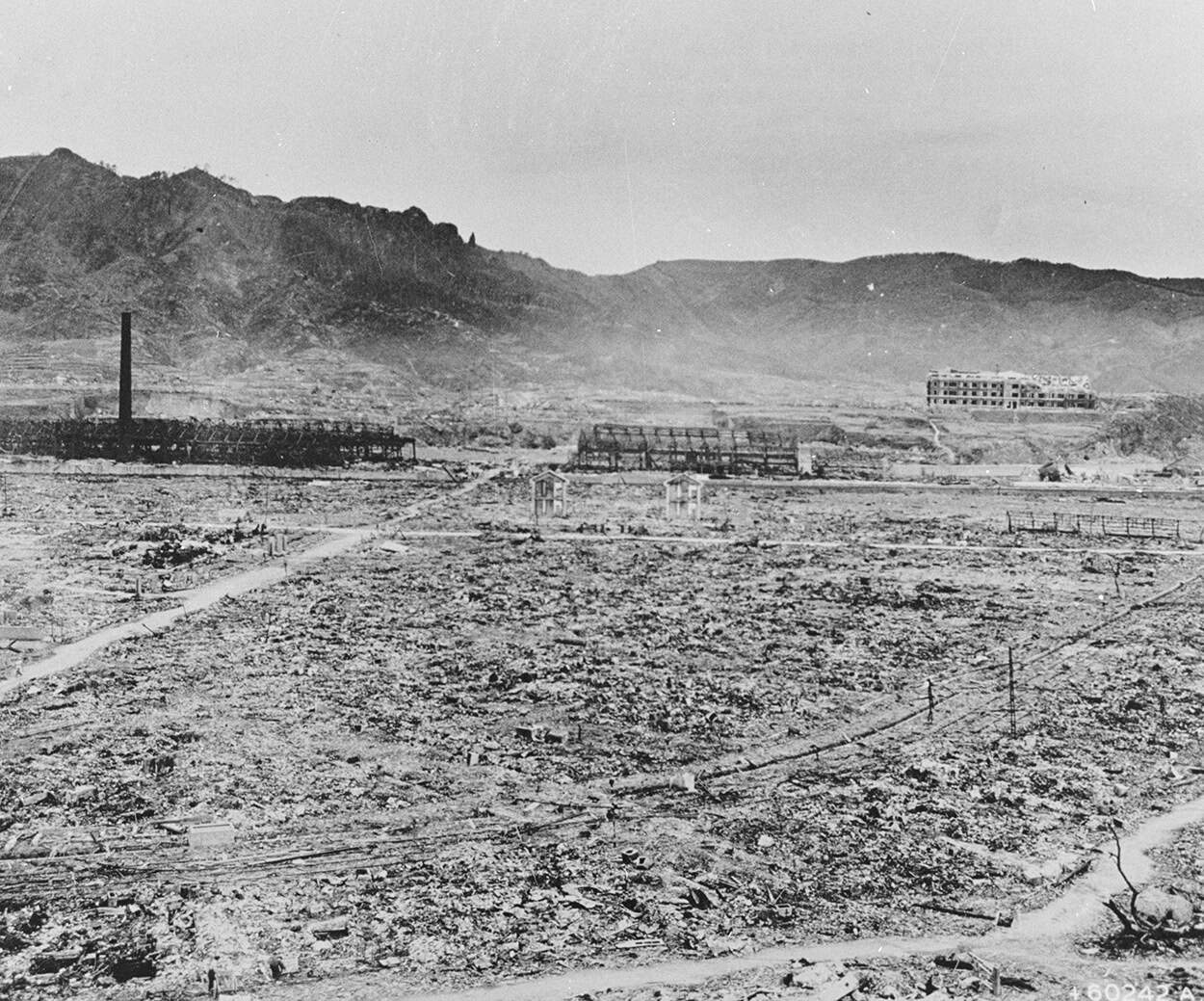

Impact of the Raid At Nagasaki

Impact of the Raid At Nagasaki

(Courtesy of the National Archives Records Administration 342-fh-3aa )

Although dropped well off target, the bomb destroyed half of Nagasaki and claimed 70,000 lives.

On 15 August 1945, President Truman announced the formal surrender of Japan, which had received guarantees that its emperor would remain head of state. The dropping of the atomic bombs had a profound effect on the Japanese people, on those taking part and those witnessing the destruction. The ethics and military necessity of the decision to deploy nuclear weapons have been debated by historians, philosophers and spiritual leaders ever since.

Cheshire, for his part, clearly understood what he had witnessed at Nagasaki and the implications for mankind of the advent of weapons of mass destruction. He saw that this new power could be used for good or for ill and he considered nuclear proliferation inevitable. It was for this reason that he remained a firm believer in deterrence for the rest of his life.

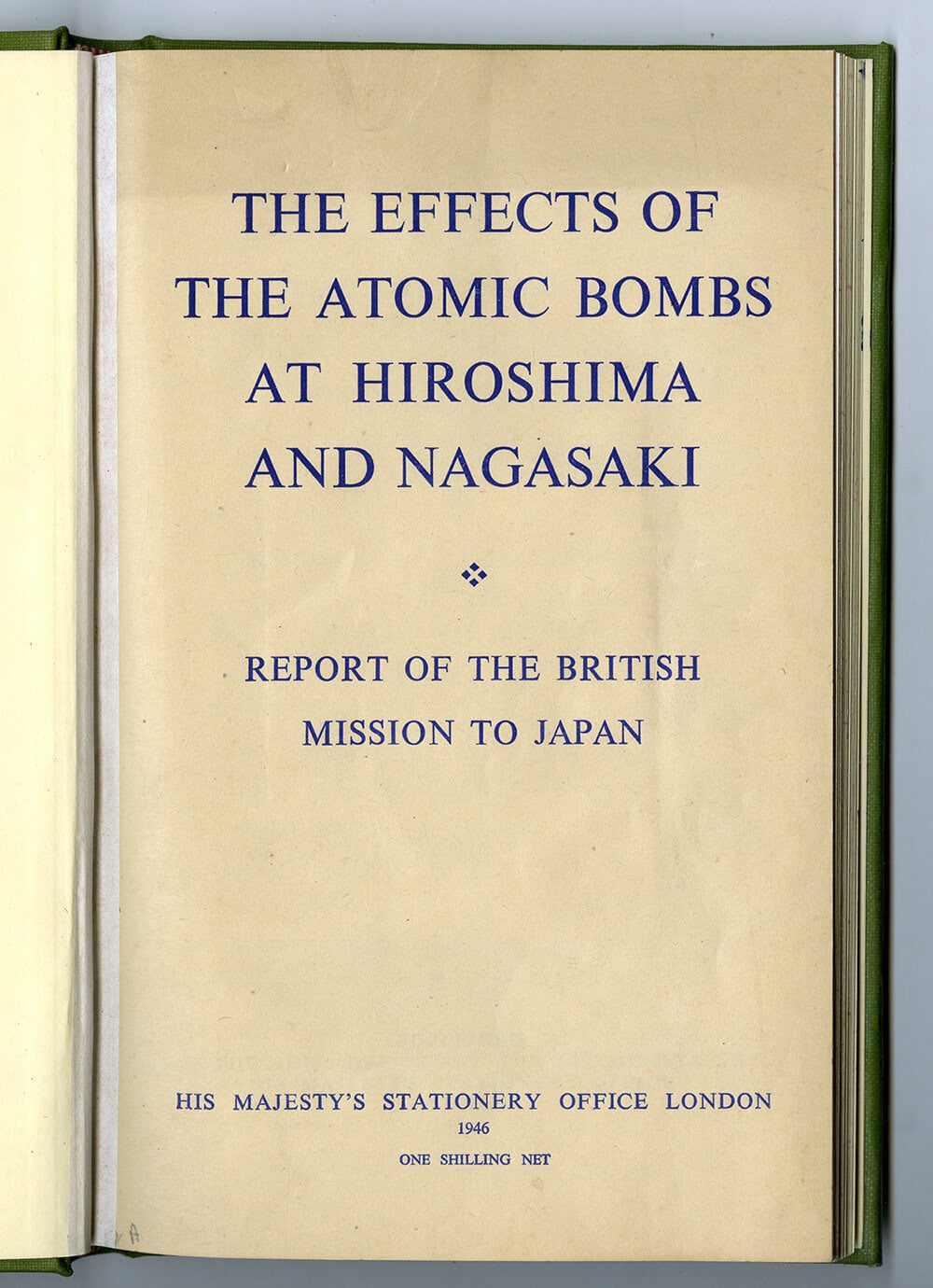

British Mission to Japan Report (RAF Museum 004751)

The raids changed the character of bombing and its scale beyond recognition. In November 1945 a British Mission to Japan spent time at Hiroshima and Nagasaki looking at the effects of the bombs. The foreword of the published report notes that ‘His Majesty’s Government consider that a full understanding of the consequences of the new form of attack may assist the United Nations Organisation in its task of securing the control of atomic energy for the common good and in abolishing the use of weapons of mass destruction’.

Cheshire retired from the RAF in January 1946. He wrote newspaper articles and delivered speeches about the ‘biological necessity’ of maintaining world peace. In February, he gave a broadcast on the BBC in which he said:

‘we are faced either with the end of this country or the end of war… to end war each one of us must play our part…it is not a responsibility we can shelve nor one that we can say belongs exclusively to the government.’

He would spend the rest of his life devoted to providing Christian care for the sick and the needy. He received the Order of Merit and was created a life peer for his humanitarian services. Lord Cheshire died on 31 July 1992 aged 74.

In 1955, on the 10th anniversary of the atomic attacks, Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park was opened. The Park’s most famous feature, the ruined Industrial Promotion Hall, or ‘A Bomb Dome’, is preserved as it was immediately after the blast on 6 August 1945. The Dome is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and receives over one million visitors every year. The Nagasaki bomb was commemorated by the unveiling of a 10 metres tall (32 feet) statue of a seated man praying for peace.

A black marble vault below the statue holds a roll of the bomb’s victims, and in 2005, Corporal Ronald Shaw’s name was added to it. Ronald Francis Shaw of Edmonton, in North London, had been captured in 1942 while serving with No. 84 Squadron RAF in Jakarta. Forced to work in an iron foundry in Nagasaki, he was one of a small number of Allied Prisoners of War killed during the raid and is buried along with 1,800 other Commonwealth servicemen at the CWGC Cemetery at Yokohama. Japanese historian Shigeaki Mori, who survived the Hiroshima attack as a boy, managed to trace Ronald’s family to Leigh-on-Sea in Essex. The family gave their blessing to his inclusion on the roll and said they hoped to visit Nagasaki one day.

Further Reading

- ‘No Passing Glory: The Full & Authentic Biography of Group Captain Cheshire VC, DSO DFC’ Andrew Boyle (Collins, 1955)

- ‘The Light of Many Suns’, Leonard Cheshire (Methuen, 1985)

- ‘Cheshire: The Biography of Leonard Cheshire, VC, OM’, Richard Morris (Viking, 2000)

- ‘Forgotten Armies: Britain’s Asian Empire and the War with Japan’, Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper (Allen Lane, 2004)

- ‘Among the Dead Cities: Was the Allied Bombing of Civilians in WWII a Necessity or a Crime?’, A.C. Grayling (Bloomsbury, 2006)

- ‘Prisoners of History: What Monuments to the Second World War Tell Us About Our History and Ourselves’, Keith Lowe (William Collins, 2020)

Relevant displays at the RAF Museum

- The RAF Museum’s Youth Panel are exploring the topic of the War in the Far East to mark VJ Day 80. Their temporary exhibition can be seen in Hangar 6 at our London site

- To explore more about the atomic era visit the RAF Museum’s National Cold War exhibition at our Midlands site

- Visit our Vulcan in Hangar 5 at the Museum’s London site and learn more about the RAF’s nuclear deterrent role and its V Force.